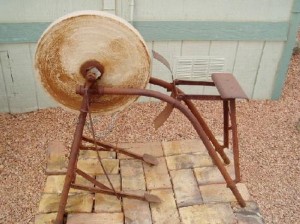

Employee productivity is often paradoxical. Which explains why it’s so tough to get it right from an employer perspective. It all stems from the counterintuitive truth that how productive you are while at the office is largely dependent on what you do away from the office to prepare your mind and body for workplace challenges. That truth often clashes with an employment mindset based on the traditional American grindstone mentality – employers often think the key to productivity involves keeping shoulders to the wheel.

Working hard is both birthright and touchstone in American culture. Statistically, only one nation (Japan) works employees harder than the United States. Not surprisingly, American workers produce efficiently and effectively. But at what cost? And could we get more productivity out of the hours our employees spend at work? At what point does working harder produce fewer returns?

Many businesses are already operating at the point of diminishing returns – that is, more effort produces worse results, not better. What most post-recession businesses need is a fundamental shift in their approaches to old and new industry-specific challenges, not marginal and incremental adjustments to a tired modus operandi.

“Just like this, only better, and with fewer resources” is pure madness. It’s an even crazier manifestation of Einstein’s definition of insanity (repeating an action with the expectation of a different outcome). But it’s the approach many business owners have taken in response to the apparent scarcity confronting them.

We’ve learned, in this regard, that conventional wisdom really isn’t. Slowing down often gets you there infinitely faster. I have never regretted taking time to gain perspective on a workplace challenge, because it has unfailingly produced a better approach to solving the problem.

Just like in art and in life, perspective on business problems only comes by adding two ingredients: time and distance. You can’t understand the nature of a thing with a limited viewpoint of it – physically or conceptually. Only with distance, and the time to observe, does the broader context emerge. More often than not, that broader context also contains the key to solving the short-term problem – or proves it to be irrelevant to attaining the business goals you’re serving. But the view from the grindstone doesn’t permit significant insight.

How does that truth translate to a systematic approach to enhancing long-term employee productivity? This is the hard part. You have to expect your employees to be at work less. You have to provide time and means for other life activities.

And you have to promote destination vacations among your workforce. Getting away from work isn’t enough – in order to restore perspective and productivity, employees have to get away from the daily rigors of the rest of their lives as well.

If you’re having a hard time convincing a frustrated CFO or CEO that when employees go away on vacation, they come back better and more productive, here are a few facts & figures to help:

- 82% of executives believe vacations improve productivity.

- Regular vacationers are less likely to become tense, tired, depressed, or stressed.

- Vacations improve alertness, cognitive ability, and motor skills – all of which reduce risk and improve productivity.

- Vacations spark creativity, innovation, and inspiration.

- Vacations prevent burnout.

- Employees who take regular vacations are happier, more content with their work situation, more productive, and less likely to make mistakes.

Without time and distance from the daily grind, workers are unable to gain perspective, develop new coping strategies, nurture important relationships, or restore motivation and dedication to their work.

Is time away really that important? Yes. One of the premier New York design firms takes an entire year off every seven years. They view it as their strategic advantage. And consider that both the iPod and the yellow sticky were invented on vacation.

Productivity is much more than work hours thrown at a problem. Quality bests quantity more often than not. It pays to take a closer look at the wonderful paradox of doing more, and doing it better, by doing less.